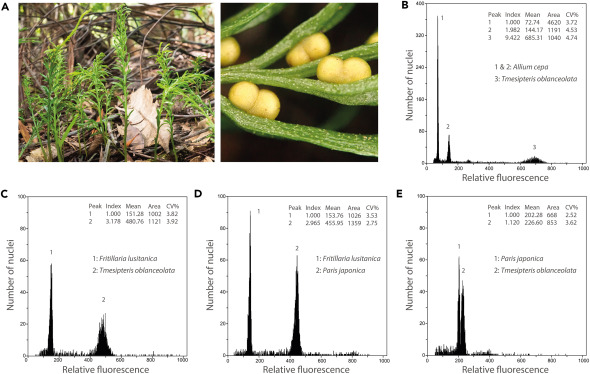

Within the unassuming foliage of a fern-like plant lies an astonishing revelation: it harbors the most massive genome ever uncovered, surpassing the human genome by over 50 times.

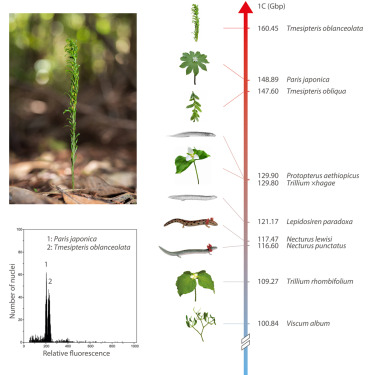

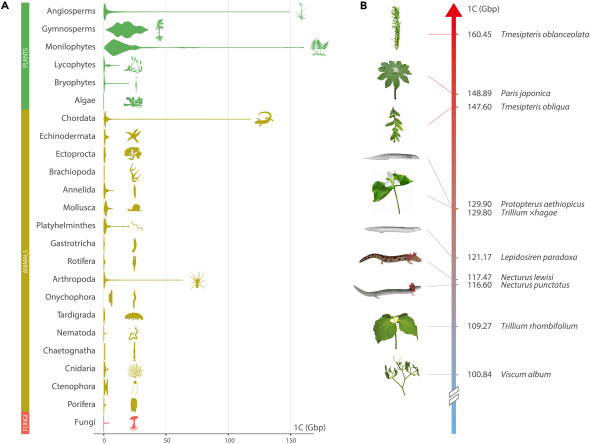

Dubbed Tmesipteris oblanceolata, this plant boasts a staggering 160 billion base pairs, the fundamental units of DNA. This surpasses the previous record holder, Paris japonica, by 11 billion base pairs and dwarfs even the marbled lungfish, Protopterus aethiopicus, which held the title for the largest animal genome. These findings were recently published in iScience.

Jaume Pellicer, a co-author of the study and evolutionary biologist at the Botanical Institute of Barcelona, Spain, expressed surprise at this discovery, having previously believed that the genome size limit had been reached with the discovery of P. japonica’s colossal genome.

This botanical behemoth, indigenous to New Caledonia and nearby South Pacific archipelagos, belongs to a species known as the fork fern. The sheer magnitude of its genetic material raises questions about how the plant effectively manages its DNA.

The evolutionary reasons behind the proliferation of base pairs in an organism remain a subject of inquiry. While a larger genome typically demands more resources for DNA replication and maintenance, organisms in stable environments with minimal competition may tolerate the burden.

This might explain the fork fern’s substantial genome size.

Despite speculation, modern sequencing techniques may struggle to decode the fork fern’s genome comprehensively. Even if sequenced, assembling the data poses computational challenges that must accurately reflect biological processes.

Unlocking the secrets of enormous genomes could offer valuable insights into how genome size influences an organism’s habitat range, environmental adaptation, and resilience to climate change, regardless of specific genetic sequences.

The significance of this discovery, highlights the potential lessons hidden within a seemingly insignificant plant.