Grizzly-polar bear hybrids, often referred to as “grolar bears” or “pizzly bears,” are rare yet fascinating examples of crossbreeding between two iconic bear species—the polar bear (Ursus maritimus) and the grizzly bear (Ursus arctos). These hybrids have gained attention in recent years, both in captivity and the wild, as climate change brings the territories of these typically separate species closer together.

The grizzly-polar bear hybrid, known scientifically as Ursus maritimus × Ursus arctos, was first confirmed in the wild in 2006 when DNA tests on a bear shot near Sachs Harbour in the Canadian Arctic revealed its hybrid status. This discovery surprised researchers, as hybrids between these two species were largely hypothetical before this point. While zoos had previously documented hybrids in captivity, this case marked the first time such an animal was confirmed in the wild.

Since then, eight confirmed hybrids have been discovered, all traced back to a single female polar bear. Genetic analysis has revealed that these hybrids are the result of grizzly bear fathers mating with polar bear mothers, and the phenomenon has sparked interest among scientists. Not only does this represent a rare case of interspecies breeding, but it also raises important questions about how climate change is impacting wildlife.

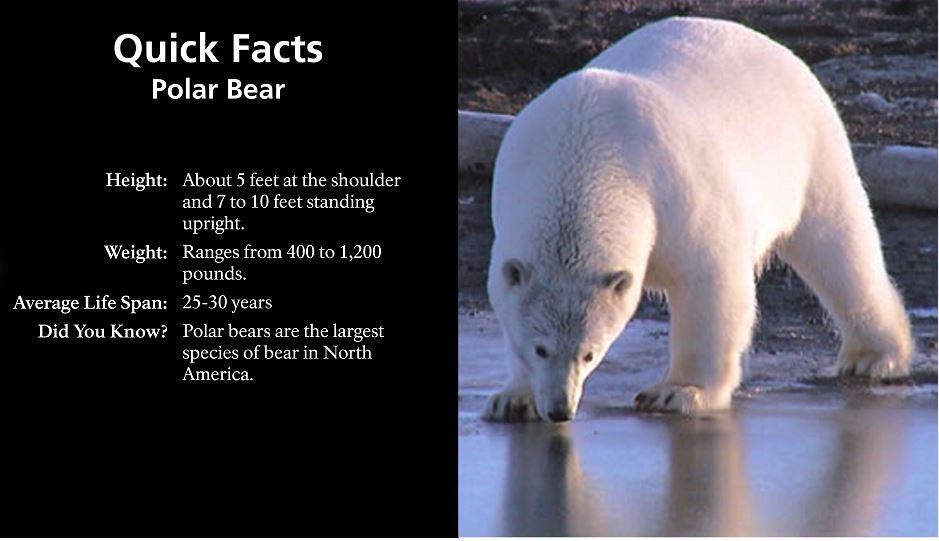

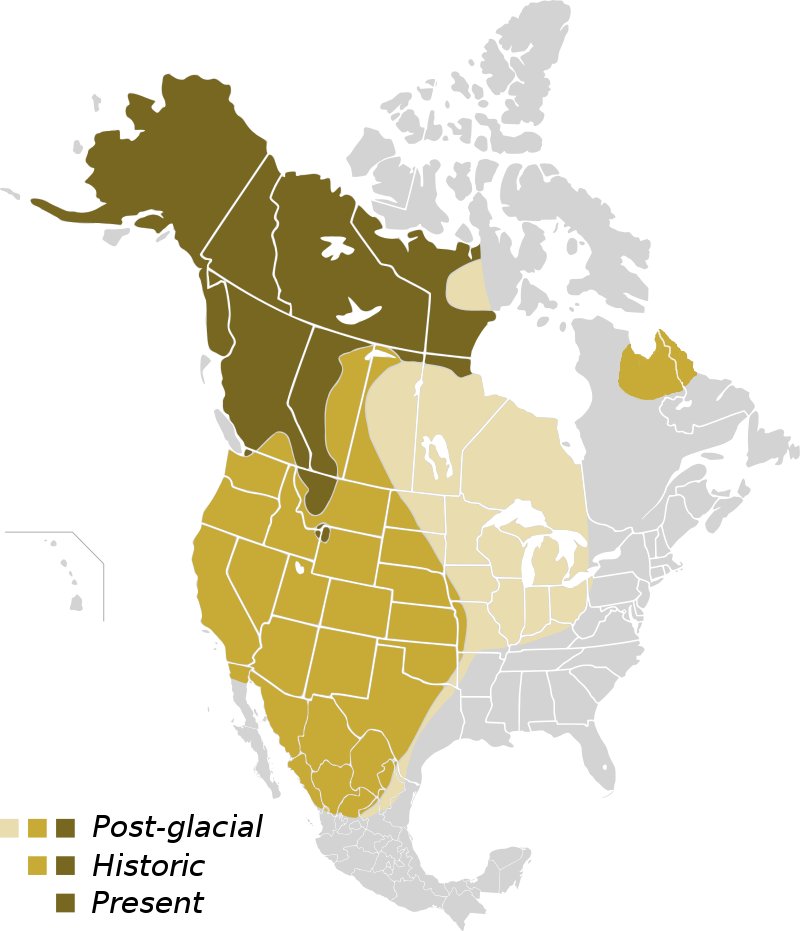

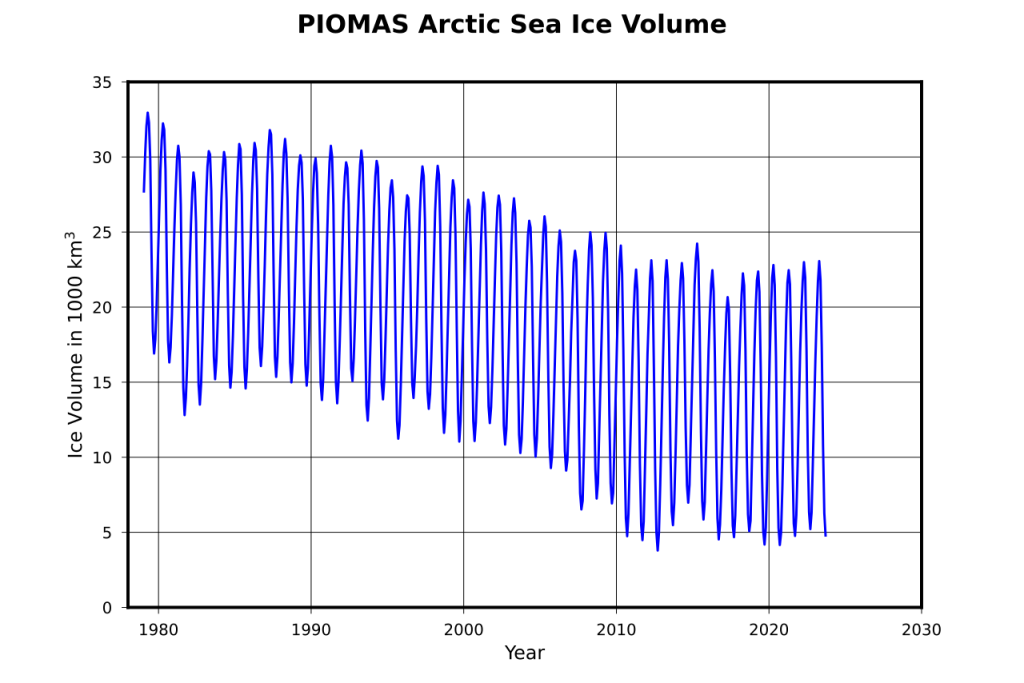

Theories about the rise in hybrids have evolved over time. One explanation involves the expansion of grizzly bear territory due to changing climates. As warmer temperatures reduce the amount of sea ice, polar bears are being forced to spend more time on land, where their paths increasingly cross with grizzlies. At the same time, as grizzly populations grow, males may range further from their traditional habitats in search of food or mates.

The scarcity of food resources in the Arctic is another possible factor contributing to hybridization. Grizzly bears, typically herbivores with a diet of berries and fish, have been observed hunting seals in polar bear territory—an unusual shift that underscores the effects of changing ecosystems. Proximity to each other while hunting may lead to mating between the two species.

The first documented grizzly-polar bear hybrid was shot by Idaho hunter Jim Martell near Sachs Harbour in 2006. Initially thought to be a polar bear, the bear had physical characteristics that stood out—long claws, a shallow face, and brown patches around its eyes and nose, along with the creamy white fur typical of polar bears. DNA testing confirmed that the bear was a hybrid, with a grizzly father and polar bear mother, making it the first confirmed wild hybrid of its kind.

Subsequent sightings and captures of hybrids have revealed a complex genetic web. Between 2012 and 2014, six more hybrids were documented, some of which were the offspring of earlier hybrids. These second-generation hybrids, known as “backcross” hybrids, demonstrate that interbreeding between polar bears and grizzlies may not be an isolated event but rather an ongoing phenomenon.

Interestingly, while these hybrids physically exhibit traits of both species—combining the larger bodies of polar bears with the broader heads of grizzlies—their behavior leans more toward that of polar bears. For example, hybrids have been observed stomping toys in a manner reminiscent of how polar bears break ice or hurl prey. This behavioral overlap highlights the complexity of cross-species traits and how such hybrids may adapt to their changing environment.

While the exact reasons for the rise in grizzly-polar bear hybrids remain uncertain, the connection to climate change is undeniable. As sea ice continues to melt and force polar bears further inland, their encounters with grizzly bears may become more frequent, leading to more hybridization. This shift also brings new challenges for both species, as their respective hunting grounds and food sources dwindle.

Some scientists worry that continued hybridization could have a long-term impact on the populations of both species. Polar bears, already classified as vulnerable due to climate change, may face even greater challenges if hybridization leads to a loss of genetic diversity. On the other hand, grizzlies appear to be adapting to their changing environment by expanding their range and diet.

Grizzly-polar bear hybrids have also been bred in captivity, providing scientists with valuable insights into how these hybrids develop. For example, in 2004, two hybrid cubs were born at the Osnabrück Zoo in Germany. These cubs exhibited a mix of physical traits from both species—long necks like polar bears, small shoulder humps like grizzlies, and a blend of hair types, some solid like grizzlies and others hollow like polar bear fur. The hybrids also demonstrated more polar bear-like behaviors, such as lying on their bellies with rear legs splayed, a stance typical of polar bears.

The emergence of grizzly-polar bear hybrids, while rare, provides a unique lens into how climate change is reshaping ecosystems and species interactions in the Arctic. These hybrids reflect both the adaptability and vulnerability of wildlife in a rapidly warming world. As scientists continue to study the genetic and behavioral characteristics of grolar bears, they offer important insights into the future of biodiversity in a changing climate.