Police in Princeton, a town east of McKinney, Texas, have uncovered a potential human trafficking operation involving several women allegedly forced to live in deplorable conditions in a rented home. Authorities believe this operation may extend far beyond Princeton, potentially involving up to 100 individuals across various locations in North Texas.

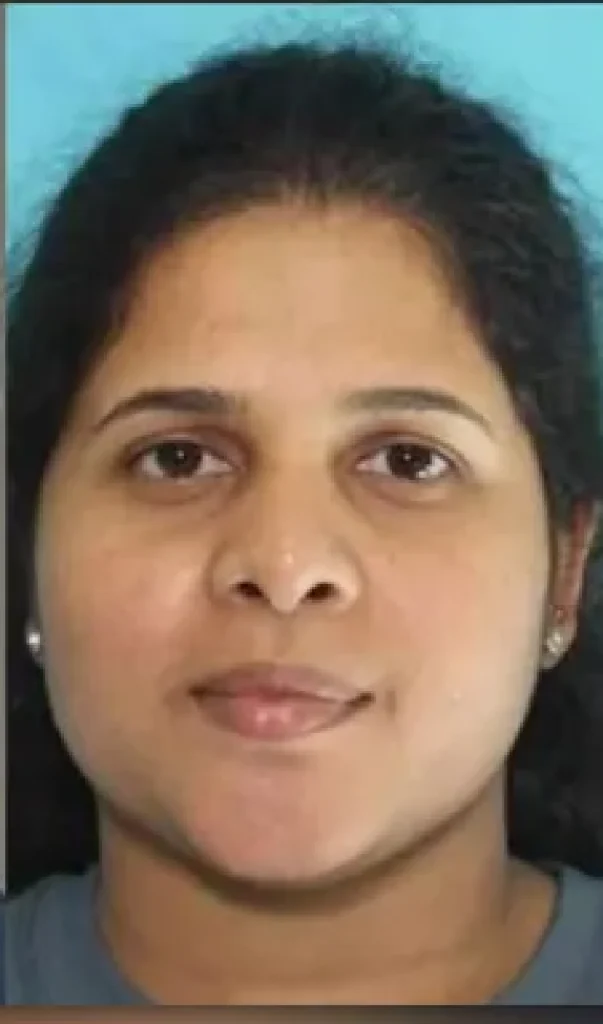

The attorney representing Santhosh Katkoori, one of the four suspects charged in connection with the case, denies his client’s involvement in human trafficking. Katkoori’s lawyer, Jeremy Rosenthal, argues that the arrest affidavit lacks evidence of force or coercion, which are key elements of human trafficking. Rosenthal insists that his client was merely helping the women with job placements and denies any criminal wrongdoing.

According to the Princeton Police Department, the women were allegedly “forced” to work for Katkoori and several “programming shell companies.” The police department’s press release details how these women were made to live in overcrowded and inadequate conditions, with minimal furniture and sleeping arrangements on the floor. Investigators discovered the situation in March but only released the details recently.

The investigation began when a pest control employee, called to treat bedbugs at the residence, noticed numerous women sleeping on the floors of multiple rooms, with only folding tables and a single air mattress for furniture. This employee’s report prompted police to investigate further, leading to the discovery of 15 women living in the house. These women, aged between 23 and 26, claimed they were brought to the house under the pretense of participating in an internship to learn Java scripting.

Katkoori, along with three other individuals, has been charged with trafficking of persons, a second-degree felony. Police believe that the women were brought to the United States, where they were taught job skills and then required to pay a significant portion of their salaries to Katkoori’s company until their “debt” was repaid. The women stated that Katkoori and his associates assisted them in creating resumes and finding employment, but once they secured jobs, they were obligated to surrender approximately 20% of their earnings.

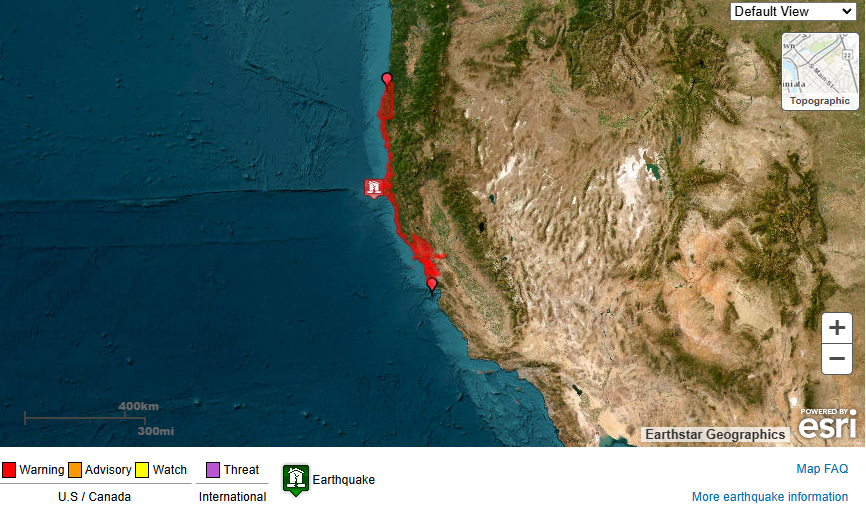

The police executed a search warrant at the Ginsburg Lane house, where they found numerous pieces of evidence, including cell phones, laptops, printers, and fraudulent documents. These findings have led investigators to believe that similar operations may be occurring in other locations, including Melissa and McKinney, where additional electronic devices and documents were seized.

Despite the serious charges, Katkoori’s attorney maintains that there is no evidence of coercion or manipulation. Rosenthal emphasized that the conditions described do not meet the legal criteria for human trafficking. He argued that helping individuals with job placements and taking a percentage of their income does not constitute human trafficking.

The arrest affidavit paints a grim picture of the living conditions within the house. The women told police that they were recruited for an internship but ended up in a situation where they were financially exploited. They described a scenario where Katkoori’s company directly received their salaries, deducted a significant portion, and paid them the remainder.

Police attempted to interview Katkoori, who initially agreed to speak but later declined. Similarly, another suspect, Chandan Dasireddy, refused to speak without an attorney. The involvement of the other suspects, Dwaraka Gunda and Anil Male, also points to a broader network of forced labor operations across North Texas.

The investigation is ongoing, and authorities are working to uncover the full extent of the operation. The charges against Katkoori and his associates are severe, and if found guilty, they could face significant legal repercussions. The case highlights the complexities and challenges in identifying and prosecuting human trafficking cases, particularly when elements of coercion and force are not immediately apparent.