As Hurricane Milton unleashed its fury on Florida, not everyone had the option to escape its path. While many residents evacuated, about 1,200 inmates at the Manatee County Jail and thousands more across other facilities like Pinellas and Lee Counties were left to face the storm’s severe impacts locked within their cells. This decision has sparked intense criticism and raised significant concerns about the treatment of incarcerated individuals during natural disasters.

Jordan Martinez, an organizer with the Campaign to Fight Toxic Prisons and the group’s Hurricane and Disaster Response Team, discussed the conditions and decisions that affect incarcerated people during such crises in an interview with Democracy Now. According to Martinez, the approach to hurricane preparedness and inmate safety in Florida reflects a disturbing norm that prioritizes infrastructure over human lives.

“The fact that they are unable to evacuate people in mandatory evacuation zones goes to show the complete lack of prioritization of the lives of incarcerated people during hurricanes,” Martinez stated during the Democracy Now interview. He highlighted that the most dangerous aspects of hurricanes for inmates often come after the initial storm surge, which can destroy essential facility operations like power and water supply, worsening conditions for those trapped inside.

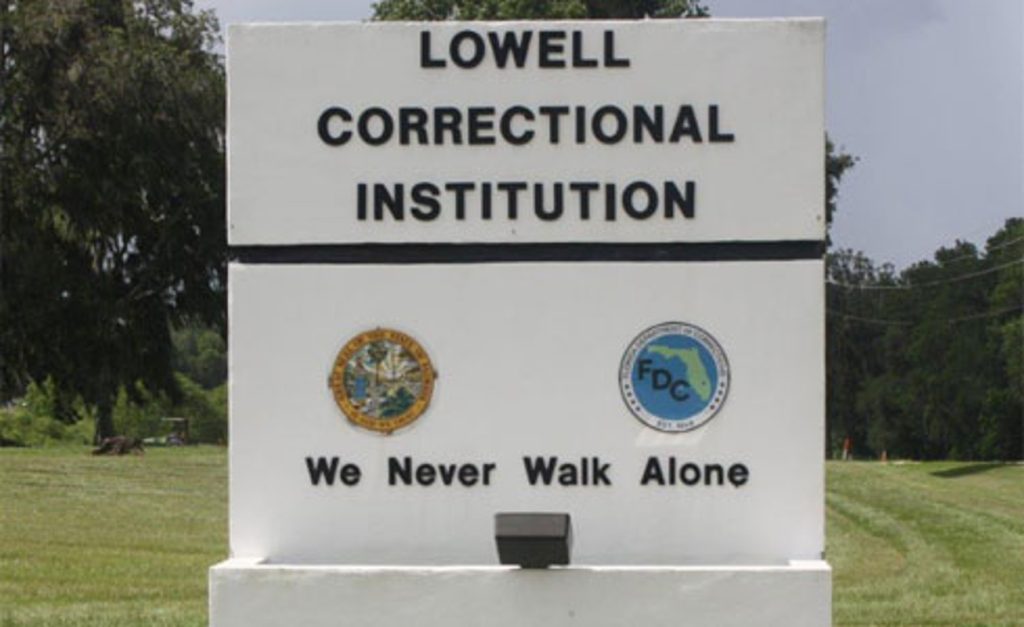

Martinez also criticized the superficial evacuation efforts, which he describes as merely relocating inmates within the same vulnerable areas or across short distances that do not offer genuine safety. “For example, Lowell Work Camp, part of the Lowell Correctional Institution women’s prison, evacuated inmates dozens of yards away to another part of the same institution. We’re seeing this fiction being raised by the Florida Department of Corrections as well as the county sheriffs,” he explained to Democracy Now.

The failure to evacuate or adequately protect inmates during Hurricane Milton is part of a broader issue, according to Martinez, where incarcerated people are forced to endure harsh conditions while being used for labor in the aftermath of disasters. “It’s part of the fiction that the sheriffs and officials in Florida like to spin to project a sense of confidence in the face of conditions that are entirely unpredictable in hurricane situations,” he noted during the interview.

Martinez calls for a significant change in how emergency preparedness is handled in correctional facilities. “We need mandatory, in-place rules and regulations during evacuations when a certain category of hurricane is coming in, that require and force state and local county officials to have evacuation plans in preparation, in advance,” he insisted in his discussion with Democracy Now. The fact that no reported deaths occurred during Milton is simply a stroke of luck. Florida may not be that lucky next time.

The stark discrepancies in safety measures between the general population and incarcerated individuals during Hurricane Milton underscore a deep-seated issue within disaster management and correctional facility operations. Martinez and his team continue to advocate for the rights and safety of incarcerated people, hoping that future responses will prioritize human lives over logistical convenience.