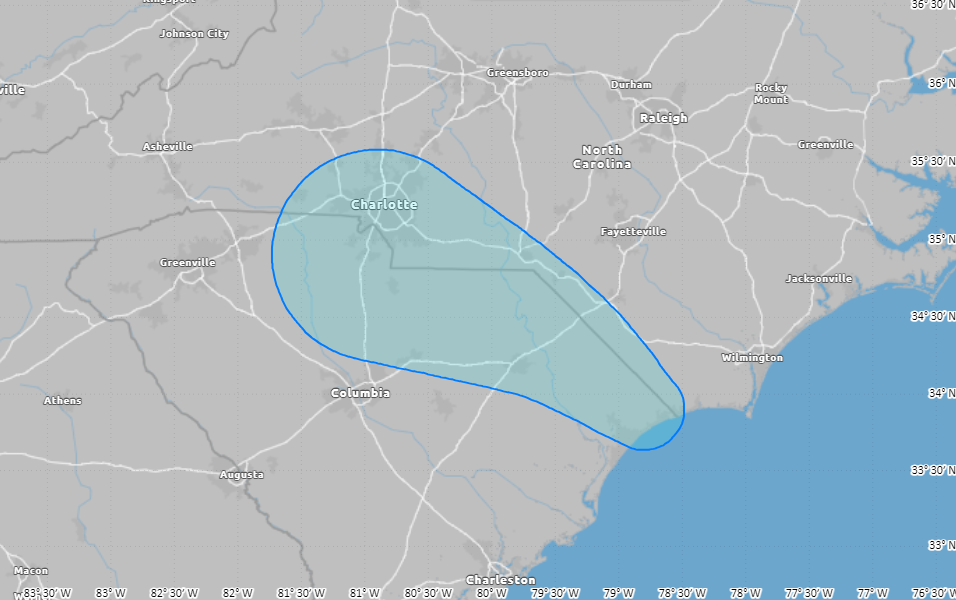

Once rare and almost unimaginable, “once-in-a-thousand-year” rain events are becoming more frequent as a result of climate change. Southeastern North Carolina recently experienced such an extreme event when the towns of Carolina Beach, Boiling Springs Lakes, and Southport were hit with over 18 inches of rain in just 12 hours. The National Weather Service (NWS) in Wilmington described this deluge as a thousand-year occurrence, a rainfall level that should only be seen once every millennium. The resulting flash flooding was life-threatening, with some areas under three feet of water, and the storm brought with it gusty winds that made conditions even more perilous.

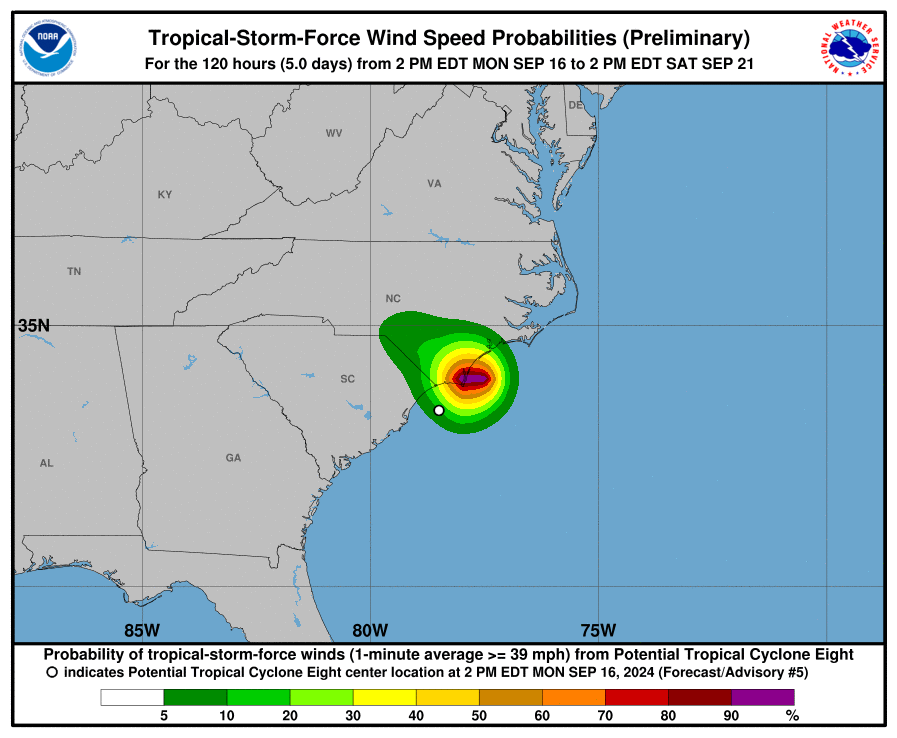

The storm, known as Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight, carried the power of a tropical storm, even though its center wasn’t fully organized. With sustained winds exceeding 39 mph and a steady downpour, this weather system highlighted a growing pattern of extreme storms in the region. Such events are becoming increasingly common, not just in the Carolinas, but across the United States and around the world. Research published in Nature Communications found that climate change has already doubled the likelihood of extreme rain events in many parts of the U.S., a trend likely to intensify as temperatures continue to rise .

Climate change is playing a significant role in driving these extreme rain events. Warmer global temperatures mean that the atmosphere can hold more moisture, and when storms form, they have access to greater amounts of water vapor. This leads to heavier precipitation, as was seen in the recent North Carolina storm. The rain fell fast and furiously, overwhelming local infrastructure and flooding homes and businesses. A study published in Nature revealed that increased atmospheric moisture due to global warming has already increased the intensity of heavy rainfall events globally by 3% to 15%, depending on the region .

Warmer ocean temperatures are also exacerbating these storms. As the oceans heat up, more water evaporates, fueling storms with additional moisture. When tropical systems like Potential Tropical Cyclone Eight develop over warmer waters, they absorb more energy, which translates into stronger, more destructive rainfall when they make landfall. The Atlantic Ocean has seen significant warming, contributing to the increased frequency of powerful storms hitting the southeastern United States in recent years. Research in Nature supports this, showing that the intensification of storms is linked to warmer sea surface temperatures driven by climate change .

What once seemed like a statistical anomaly is now happening with alarming regularity. Just last summer, the United States experienced three different “once-in-a-thousand-year” rain events in the span of a single week. These storms, with their devastating rainfall totals and widespread flooding, are no longer isolated incidents. They are part of a broader shift in the Earth’s climate that is fundamentally changing weather patterns across the globe, and regions once thought immune to these extreme weather events are now finding themselves at risk. According to a report, extreme rain events are expected to increase by 20-30% in the next few decades if climate change continues at its current pace .

The impact of these extreme weather events is profound. In North Carolina, the recent storm caused flash flooding, blocked roads, and left communities grappling with the aftermath. Rivers in the area rose to dangerous levels, and forecasters warned that further flooding was possible as the storm system lingered. In coastal areas, elevated tides associated with the full moon and strong winds created additional challenges, causing minor to moderate coastal flooding. The damage was widespread, and the threat of more intense storms looms large as the climate continues to warm.

For communities, the costs of dealing with these increasingly frequent extreme weather events are enormous. Infrastructure that was designed for weather patterns of the past is proving inadequate in the face of modern storms. Roads, bridges, and stormwater systems are failing under the strain of unprecedented rainfall, and the consequences for both urban and rural areas are severe. In some cases, entire neighborhoods are submerged, and the recovery process is long and costly, both in terms of financial resources and the toll on residents’ lives.

As climate change accelerates, the need to adapt to this new reality is becoming increasingly urgent. Governments, municipalities, and individuals will have to make substantial changes to mitigate the impacts of these extreme weather events. While efforts to combat the root causes of climate change are essential, there is also a growing recognition that adaptation strategies must be put in place to protect communities from the immediate dangers of once-unthinkable storms. The cost of inaction will only grow as these storms become more frequent.

Looking ahead, scientists predict that extreme rain events will continue to increase in both frequency and severity. The trend is clear: warmer temperatures, more moisture in the atmosphere, and disrupted weather patterns are creating the conditions for more powerful storms. This pattern shows no signs of reversing unless significant global action is taken to address climate change. The question now is not if these storms will happen again, but when and where the next catastrophic rainfall event will strike.

The recent storm in North Carolina serves as yet another stark reminder of the challenges ahead. What was once considered a “once-in-a-thousand-year” event is becoming a regular occurrence, a sign of the new era we have entered as a result of climate change. As communities grapple with the aftermath and prepare for the future, the urgency of addressing climate change and adapting to its impacts has never been clearer.

Kunkel, K. E., et al. (2017). Long-Term Changes in Extreme Weather and Climate Events. AMS.

Gu, L., Yin, J., Gentine, P. et al. Large anomalies in future extreme precipitation sensitivity driven by atmospheric dynamics. (2023).

Gründemann, G.J., van de Giesen, N., Brunner, L. et al. Rarest rainfall events will see the greatest relative increase in magnitude under future climate change. Nature, October (2022)