Josephine County Commissioners have put a 320-acre tract of forestland known as “Pipe Fork” up for auction, a move that has alarmed environmentalists and dashed hopes of preserving the land through a previously arranged conservation deal. The Williams Community Forest Project, a local conservation group, had secured over $2 million from the Conservation Fund, along with $300,000 in community-raised funds, to purchase the land and preserve it.

However, the commissioners backed out of the deal in July, claiming that the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) could not guarantee public access or that the land wouldn’t be logged. Conservationists argue that part of Pipe Fork would have been incorporated into a Research Natural Area (RNA), ensuring its protection.

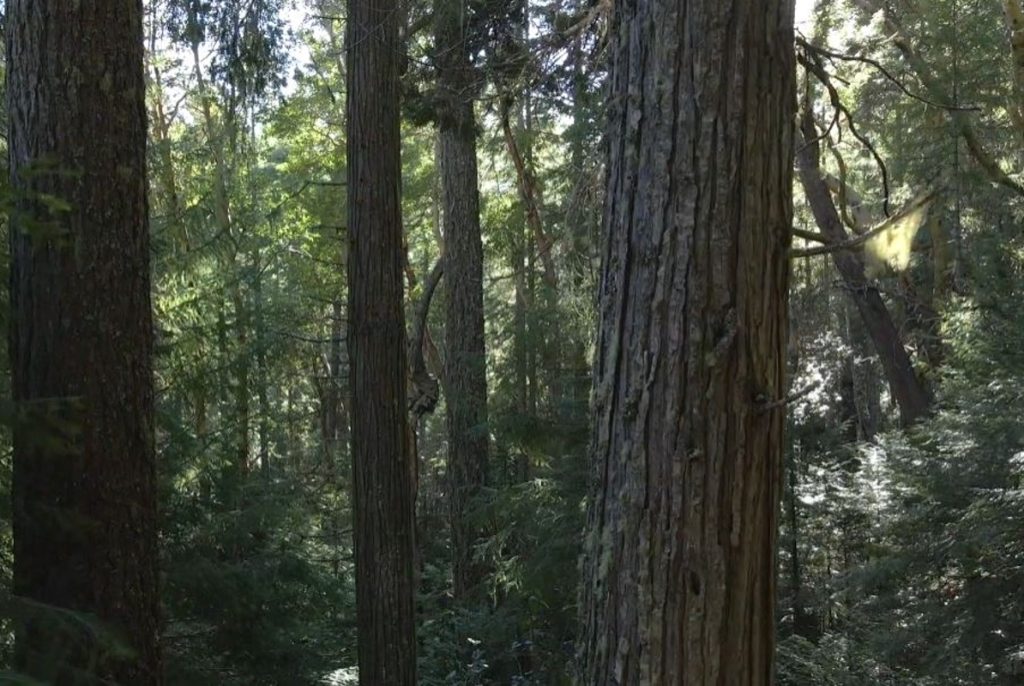

Pipe Fork is a lush, mature riparian forest located in Southern Oregon’s Klamath-Siskiyou Bioregion. Fed by pure-water springs from the ancient forests of Grayback Mountain, Pipe Fork Creek flows cold and clear year-round, providing vital water resources for farms and homes in the Williams Valley.

More importantly, the area serves as a crucial spawning and nursery habitat for chinook and coho salmon. The land has been designated as a Research Natural Area by the BLM, and its upper reaches are nominated for Federal Wild and Scenic River designation. The forest is home to rare wildlife, including Pacific fishers, martens, spotted owls, elk, bear, and rare plant species, making it a critical area for biodiversity and ecosystem health.

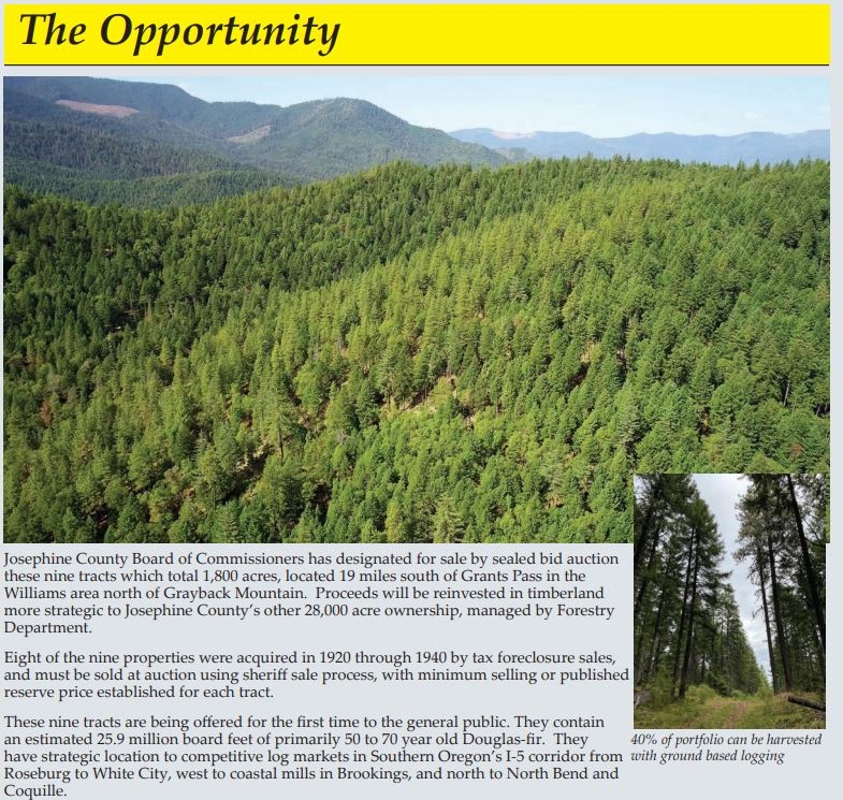

The decision to auction the land has sparked outrage, particularly due to how it is being marketed. The auction pamphlet promotes Pipe Fork as prime timberland, describing it as an “investment opportunity” with “well-stocked 50 to 70-year-old Douglas-fir” trees ready for logging.

The county’s plan includes selling the land, which encompasses both sides of Pipe Fork, and clearcutting 114 acres on the north side of the creek. Clearcutting on these steep slopes would cause lasting damage to the riparian forest, diminishing the quality and quantity of water flowing into Williams Valley and harming the habitat of numerous rare species.

Despite the setback, the Williams Community Forest Project remains determined to protect Pipe Fork. Cheryl Bruner, secretary for the group, expressed frustration over the commissioners’ decision and called on the community to help save the land. “We want people who want to conserve the land to bid on the land,” Bruner said. The group has scheduled a community meeting for October 24 to raise awareness and support for their efforts. Though the minimum bid price for the land has nearly doubled, due to it being bundled with another 280-acre tract, the conservation group is hopeful that they can raise the funds needed to compete in the November 14 auction.

The fight to save Pipe Fork represents more than just a local battle. It is a symbol of the broader tension between conservation and profit, between preserving irreplaceable natural resources and exploiting them for short-term gain. As the auction date approaches, the future of Pipe Fork—and the rare ecosystems it supports—hangs in the balance. Conservationists remain hopeful that, through collective effort, this precious old-growth forest can be saved for future generations.