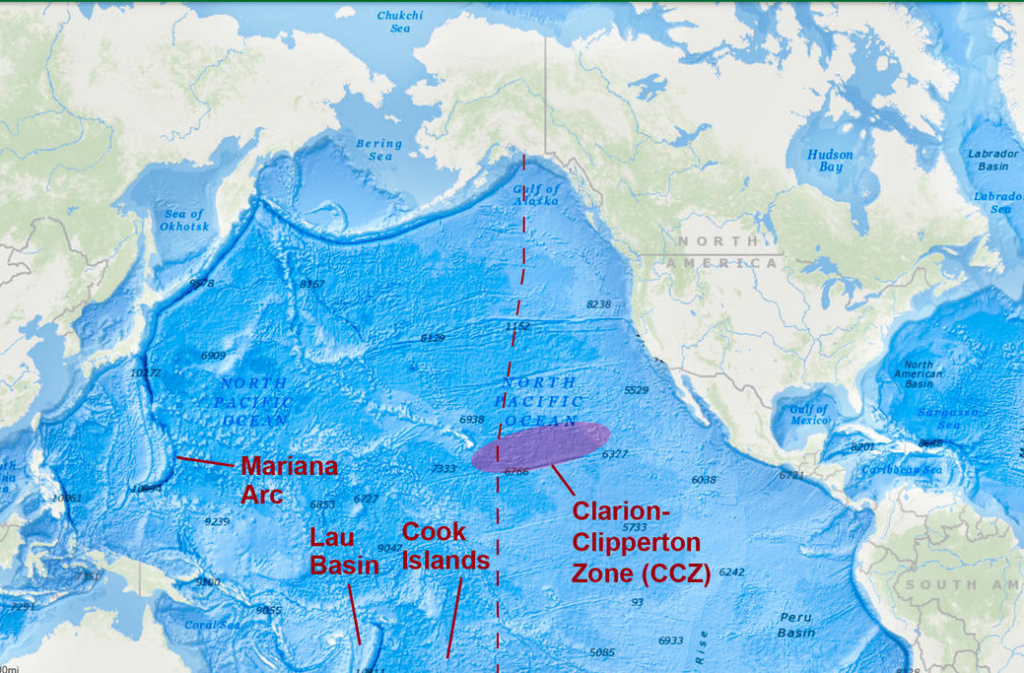

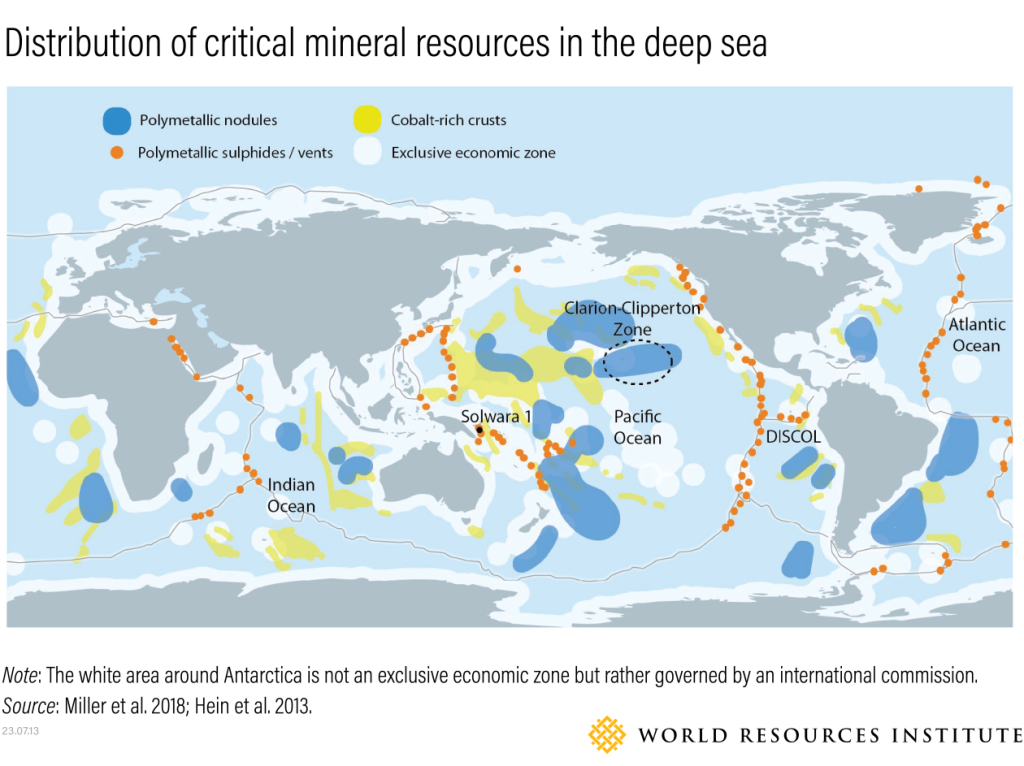

On Sunday night’s episode of Last Week Tonight, John Oliver tackled the contentious subject of deep-sea mining, with a particular focus on the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ). This Europe-sized area, located three miles beneath the Pacific Ocean between Mexico and Hawaii, is under scrutiny for its vast reserves of precious metals and unique deep-sea life. Oliver’s detailed segment shed light on the potential environmental impacts and the ongoing battle between mining companies and conservationists.

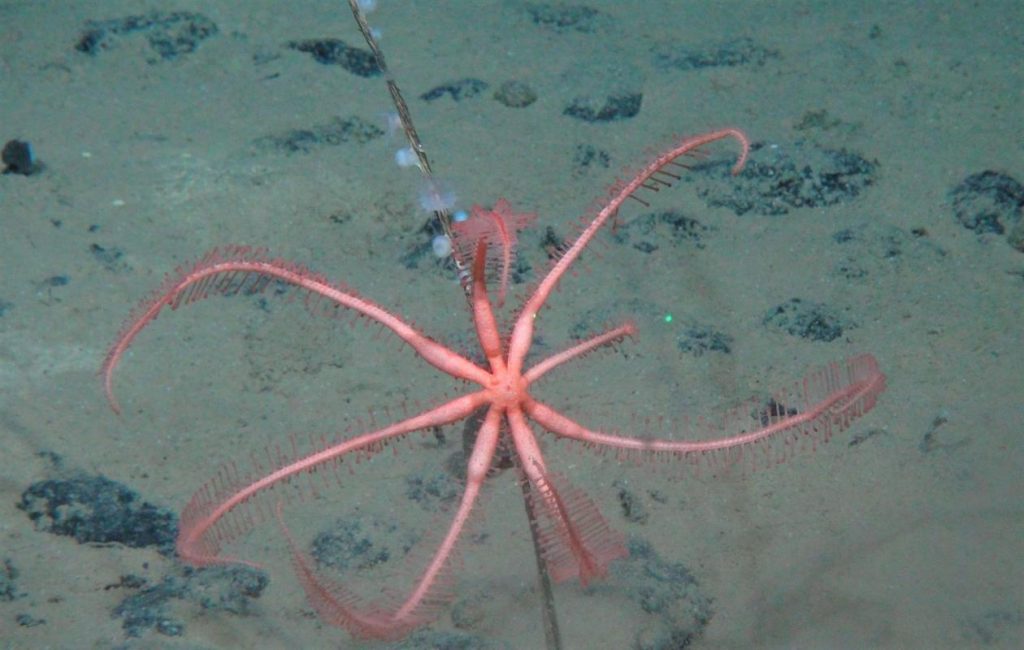

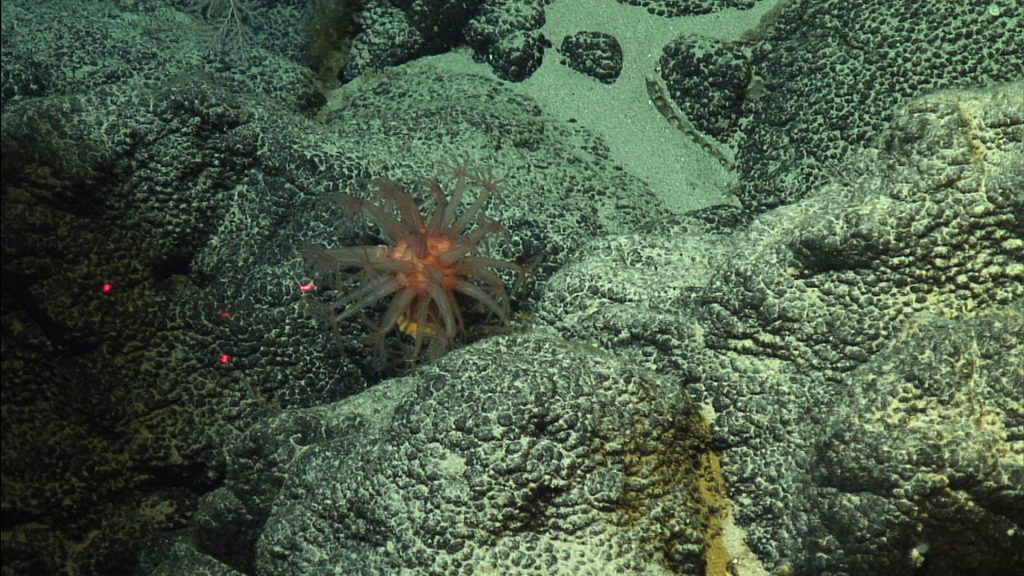

The CCZ is a dark, frigid environment where water temperatures can plunge to zero degrees Celsius. Despite its seemingly inhospitable conditions, it is home to an astonishing array of over 8,000 largely unidentified species. Among these is a fluorescent sea cucumber, whimsically named the “gummy squirrel.” “Oh, I like that a lot,” Oliver enthused. “In fact, I love that gummy squirrel so much, I want to cover it in sour dust and eat a bag of them while watching Nicole Kidman talk about the magic of the movies.”

Scientists have long known that the CCZ contains small, solid nodules rich in metals like cobalt and nickel, accumulated over millions of years. These nodules are highly sought after for their potential use in electric car batteries. Leading the charge to mine these resources is Gerard Barron, CEO of The Metals Company. Barron describes the process as akin to picking up golf balls from a driving range. “That sounds easy until you remember they’re 15,000 feet underwater,” Oliver countered, comparing it to retrieving golf balls from a grizzly bear’s delicate area.

Oliver emphasized that Barron’s analogy significantly downplays the environmental damage that mining could cause. Researchers estimate that 30-40% of the CCZ’s species live on these nodules. “Just because creatures are small doesn’t mean they aren’t important to the ecosystem,” Oliver explained. The comedian highlighted the irreversible impacts deep-sea mining could have, from microbes to the beloved gummy squirrels.

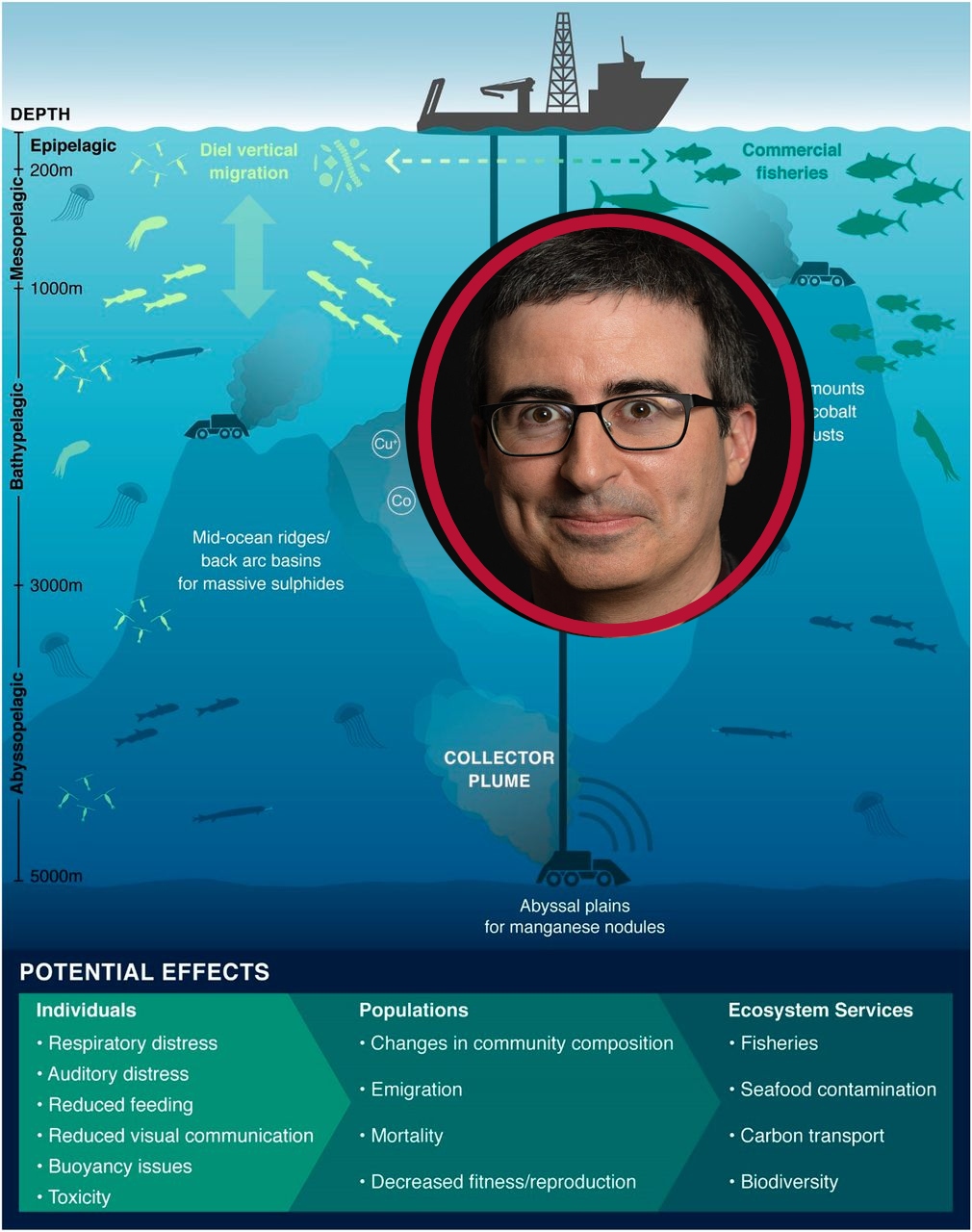

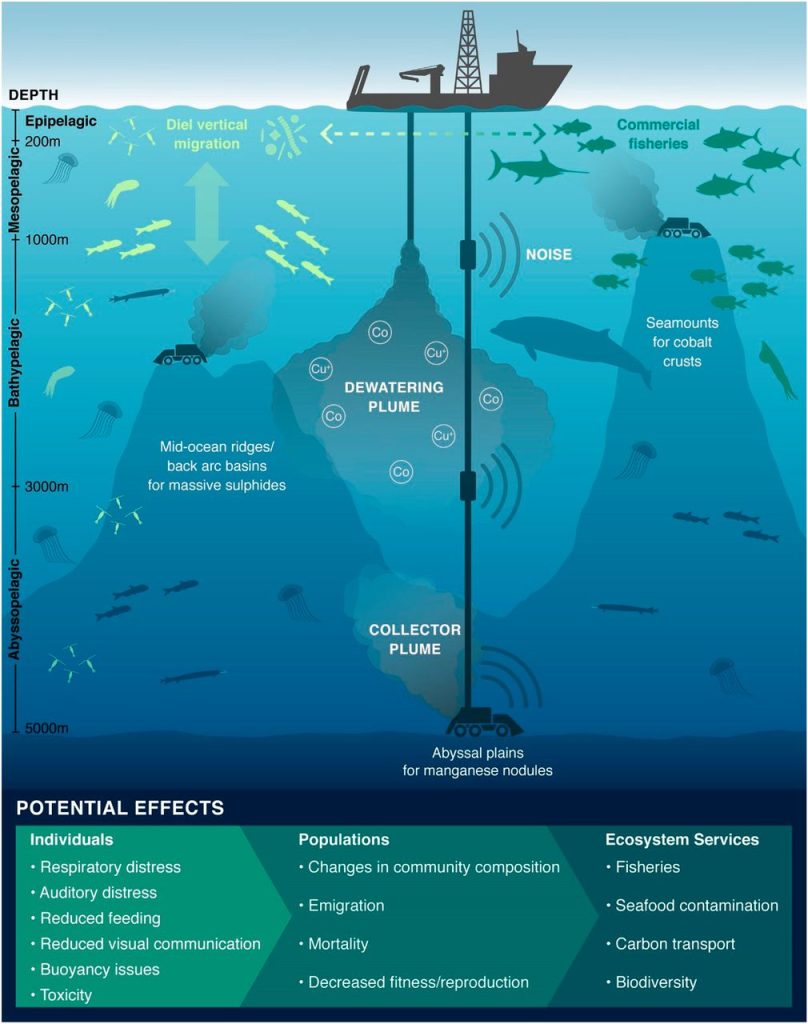

Mining operations would involve giant harvesting vehicles that create plumes of sediment, potentially burying nodule fields and suffocating anemones and sponges. These plumes could also disrupt the bioluminescence that many deep-sea creatures rely on for hunting and mating. “Think less ‘gently lifting golf balls off the driving range’ and more ‘a scene from Dune 3: Even More Sand,'” Oliver quipped.

The Metals Company argues that their commissioned research indicates minimal damage, but Oliver pointed out that independent studies suggest otherwise. One such study found that 26 years post-extraction, the ecosystem had not returned to its original state. Deep-sea mining, Oliver argued, threatens not just biodiversity but also scientific understanding and Earth’s carbon cycle, as deep-sea microbes play a crucial role in sequestering carbon.

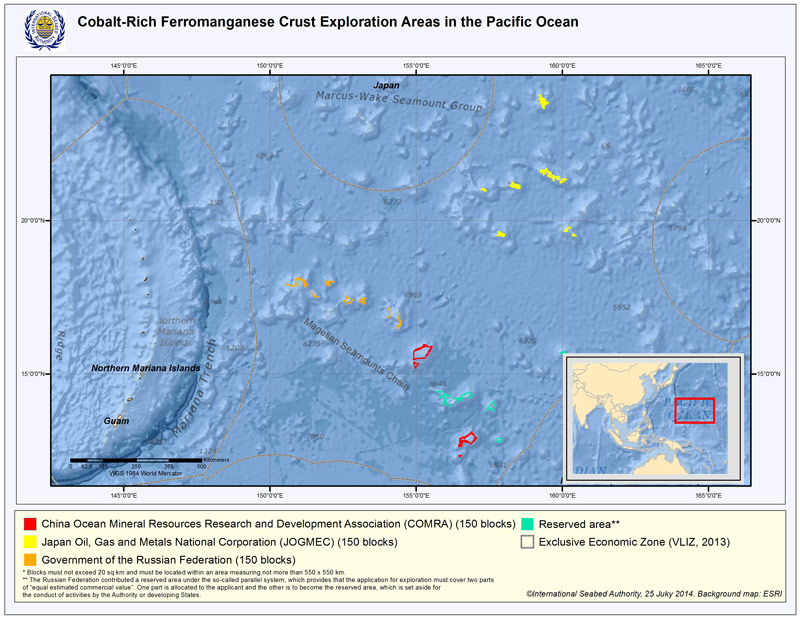

The segment also criticized the regulatory framework governing deep-sea mining. The UN’s International Seabed Authority (ISA), established in 1982, manages most of the seafloor. However, the U.S., under Reagan, refused to ratify it, and concerns persist about the agency’s impartiality. Oliver noted that the ISA’s secretary general, Michael Lodge, appeared in a promotional video for Barron’s company, raising questions about potential conflicts of interest.

The ISA is supposed to preserve half of the sea floor for smaller nations, which is how The Metals Company struck a deal with Nauru, a Pacific island nation devastated by phosphorous mining. Under the terms, Nauru would receive 0.5% of profits. “There is a clear power disparity,” Oliver said, between an international mining firm and an environmentally ravaged island with a population of just 12,000 people.

Nauru’s involvement has triggered a mechanism requiring the ISA to start accepting deep-sea mining applications even if mining regulations are not finalized. Barron expects production to begin by the first quarter of 2026. Oliver expressed skepticism about the claimed benefits of deep-sea mining, noting that new battery technologies use sodium and are moving away from using nickel and cobalt.

Oliver called for the U.S. to join other nations in demanding a precautionary moratorium on deep-sea mining and to finally join the ISA. “It’s going to take us having the patience to wait for the science on this and the discipline to actually listen to what it has to say,” he urged, highlighting the need to protect the deep ocean’s vast, unknown world from exploitation.

In the broader context of reducing greenhouse gas emissions, the demand for critical minerals is surging. However, with the environmental and ecological risks associated with deep-sea mining, the debate continues on whether this path is necessary or if alternative solutions can be pursued to meet the global demand for clean energy technologies.