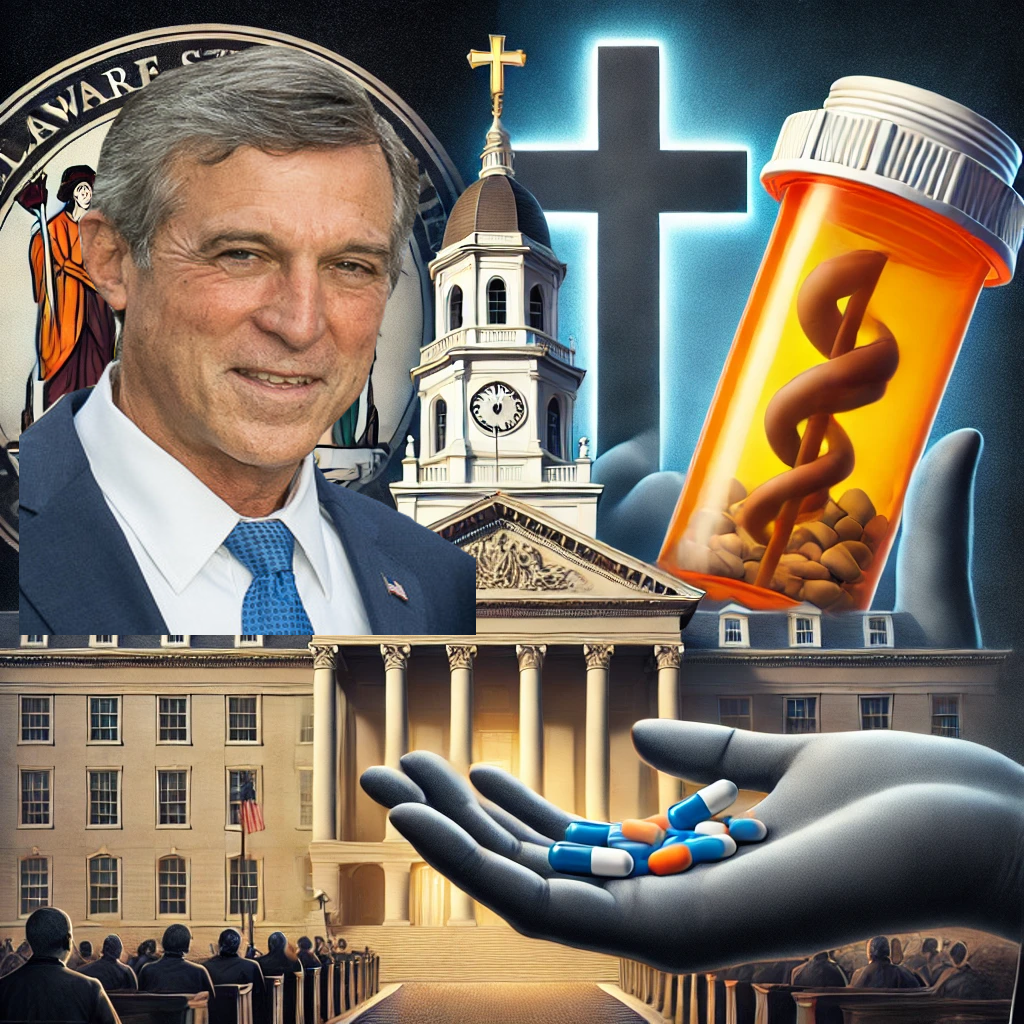

Delaware Governor John Carney vetoed House Bill 140 on September 20, 2024, blocking a long-awaited effort to allow terminally ill residents the option of medical aid in dying. The bill, which had been decades in the making, would have given Delawareans with six months or less to live the ability to choose how and when to end their lives. Instead, Carney’s moral opposition to the legislation led him to reject it, ensuring that terminally ill patients in the state will continue to face prolonged and painful deaths without this option.

House Bill 140, also known as the Ron Silverio/Heather Block End of Life Options Law, was named after two Delawareans who wanted to die on their own terms, avoiding the suffering that often comes with terminal illnesses like cancer. The bill passed both the House and Senate by narrow margins earlier this year, but Carney’s veto now prevents it from becoming law. In his veto letter, Carney, who is a Roman Catholic, explained that his personal and religious convictions played a role in his decision. “Although I understand not everyone shares my views, I am fundamentally and morally opposed to state law enabling someone, even under tragic and painful circumstances, to take their own life,” he wrote.

The deaths of Ron Silverio and Heather Block, came without the legal right to make an end-of-life decision. Supporters of the bill, including Rep. Paul Baumbach, who sponsored the legislation, expressed outrage and disappointment over the veto.

The fight to pass this bill has been nearly a decade long, and while it gained enough support to pass through the General Assembly, the opposition was fierce. The Senate vote in June was particularly close, with an 11-10 party-line vote. Many lawmakers who opposed the bill invoked religious and moral arguments, mirroring the debate surrounding abortion rights. Carney’s Roman Catholic faith was a significant factor in his moral reasoning, aligning with the Church’s traditional opposition to physician-assisted death.

While the bill’s supporters are considering a push for a veto override, the narrow margins in both chambers make it an uphill battle. The future of the legislation remains uncertain, but for now, Delaware remains on the sidelines of a national movement that seeks to provide terminally ill patients with more control over their final days.

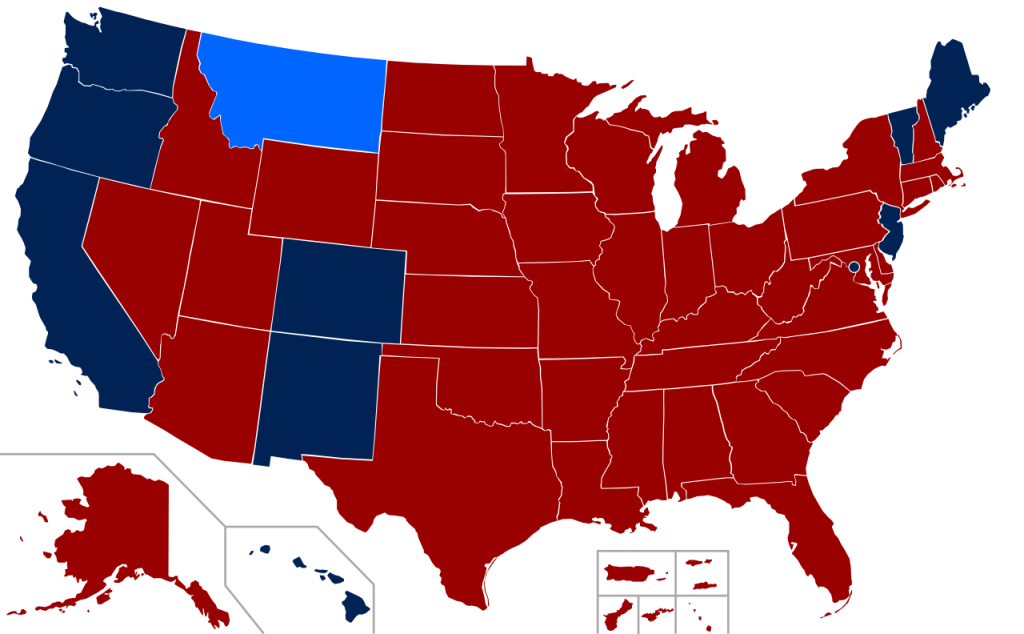

Had Delaware passed House Bill 140, it would have become the 12th state in the U.S. to legalize medical aid in dying, joining states like Oregon, California, and Colorado. These states have enacted laws that allow terminally ill patients to self-administer life-ending medication under strict conditions, including verification of their diagnosis by multiple doctors and a waiting period. The goal of these laws is to give patients the ability to avoid extreme pain and loss of dignity in their final days.

Carney’s veto also has broader implications. Terminally ill patients often require heavy sedation and pain management during their final months, a treatment that benefits pharmaceutical companies supplying these medications. Critics argue that Carney’s decision indirectly benefits Big Pharma, as patients who are denied the option to end their lives may require extensive and costly sedation to manage the unbearable pain associated with terminal conditions. In states where medical aid in dying is legal, patients have the choice to avoid prolonged suffering, reducing the need for expensive, high-dose pain medications in their final days.

As more states pass medical aid-in-dying laws, Delaware remains an outlier in this growing movement. Advocates will likely continue their efforts, but for now, terminally ill patients in Delaware will continue to face difficult and painful deaths without the legal right to end their suffering on their own terms.